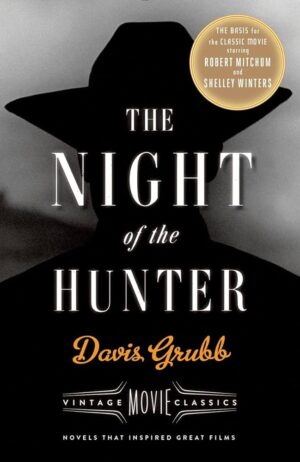

Brooding 1953 cult favourite, The Night of the Hunter by Davis Grubb is perhaps better known for its darkly expressionistic film adaptation, starring Robert Mitchum. For film fans seeking out the book, Mitchum’s charismatic, menacing performance as Harry Powell, self-proclaimed preacher and depraved soul, inevitably sears itself onto the page, a character with evil intent from the moment we first meet him, plotting to lay his hands on a bank robber’s loot. In Grubb’s nightmarish Southern Gothic cat-and-mouse tale, a classic contest of good versus evil is underway, as the preacher’s predilection for seduction, theft and murder is resisted by a lionhearted boy and his little sister.

We first meet Powell, referred to throughout as just Preacher, serving time in a Virginian penitentiary. His cellmate is the gallows-bound Ben Harper, a family man driven to bank robbery by the hard, mean times of the Great Depression. Having secretly stashed the loot with his children, John and Pearl, Ben spends the final days before his execution being unsuccessfully harangued about its whereabouts by the supposed man of God.

‘That money’s bloodied with Satan’s own curse now,’ Preacher says. Flinty-eyed and straight backed, his distinguishing feature is tattooed knuckles, H-A-T-E on the left and L-O-V-E on the right, on hands that hypnotise all he meets, their blue-lettered fingers, often resting ‘in pale, silent embrace like spiders entwined.’

When Preacher is eventually released from jail, he sets off to the dead man’s homestead to meet the bereaved Mrs Harper. God often sends him widows but this one comes with two children, little Pearl, who welcomes the idea of a new daddy, and nine-year-old John. While his fragile mother, Willa, may be ripe for seduction, John is instinctively filled with dread, his father’s secret trembling in the balance.

Darkly atmospheric, and laden with chills, thrills and malevolence, Grubb’s tale cranks up the tension as Preacher insinuates himself into the Harper’s lives and home.

‘You can never hear him coming up steps because his feet are like leaves falling, like shadows in the moonlight…’

John cannot understand why the adults in his life are unable to perceive the true character of this man they consider to be a charming newcomer. As Preacher’s covert hints become direct threats (accompanied by a six-inch, spring-bladed knife), the children must act, both to stop him discovering where the cash is cunningly hidden, and to save their own lives.

Both a climactic page-turner and considered novel of contrasts, Grubb’s portrayal of the children’s shattered innocence is compelling, the previous safety of their nursery days replaced by ‘a time of echoing and vast aloneness, when there is no one to come nor to hear…and the ticking of the old house is the cocking of the hunter’s gun.’

Corruption, as personified by the fake preacher with his unholy greed and rage, comes with subverted lust, hatred, and a murderous heart. The question is whether he can be vanquished by John and Pearl, a predicament that grips to the brilliant finale of Grubb’s eerie slice of period piece Americana.

The Night of the Hunter by Davis Grubb is published by Penguin Classics, 256 pages.