A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell is a 12-volume sequence of novels that has been lauded as one of the greatest works of 20th century English literature. The books start in the late 1920s and take us up to the 1960s, feature a huge cast of characters and offer a remarkable vision of changing social history, a deftly sustained narrative, some wonderfully memorable characters and a stark vision of the impact that time wreaks on our lives.

Anthony Powell went to Eton and Oxford a century ago (when that wasn’t something to be faintly embarrassed about), was embedded in the traditional literary establishment, mixed with many of the great writers, musicians and artists of the time as well as an array of landed gentry and socialites. Inevitably this world is reflected in his novels and in fact many of his characters are said to be based on real figures including George Orwell, Constant Lambert and the Pakenhams. The boisterous cabaret musician Heather Hopkins in one of the books refers cuttingly to ‘Parties, picnics and balls; balls, parties and picnics,’ and any modern reader coming to these novels for the first time may well bridle at the privileged milieu into which we are thrust in the early books of the sequence. Persevere though (the same criticism was after all levelled at Jane Austen) for Powell’s central subject is – as he declared – ‘human beings behaving’.

Our narrator is Nick Jenkins, a schoolboy in the first novel, A Question of Upbringing, who shares a study with the clever and anarchic Charles Stringham and the rebellious Peter Templar. He records how they rag their headmaster and mimic an unattractive boy who doesn’t quite fit in: the awkward, ill-dressed but creepily ambitious Kenneth Widmerpool.

By the second and third novels the friends have gone their separate ways and Jenkins has moved from university to the world of high society balls and the marriage market. He also starts to make his way in more artistic, bohemian circles where he falls in with the down-at-heel but talented musician Hugh Moreland and the left-wing publishing coterie of JG Quiggin and Mark Members.

In the three war novels (my personal favourites) he starts off as a middle-ranking officer in a Welsh regiment and later lands a desk job in Whitehall where he comes across the femme fatale Pamela Flitton who is to play a major role in the final four novels. After the war the action returns to literary London via Venice, with the final title, Hearing Secret Harmonies, more than hinting at a new age of occultism and a young generation taking over from the now elderly Jenkins and his contemporaries.

Always the sharp observer, Jenkins excels as a detached yet empathetic onlooker, managing to elicit confessions from others but rarely letting the reader into the details of his own life. Each new novel brings with it both new characters and appearances of old ones – as in life, we may not see people for years and then suddenly we come across them again, the same but different. Widmerpool surfaces repeatedly, each time more odious, with the arrogance and disregard for others brought on by worldly success and steely monomaniacal determination.

‘War is a great opportunity for everyone to find his own level. I am a major – you are a second lieutenant – he [Stringham] is a private’.

Some of our favourite characters die off shockingly early. Jenkins’ first great love, Jean, is often heard about while off-stage, her marriages and betrayals reported by minor characters until she reappears in a late book in an entirely new incarnation. Even those with walk-on parts pop up again: a young charismatic violinist seen in Book 5 has white hair when he is spotted again in Book 12. Each novel tends to focus on just a few events that bring the characters together and afford the sensitive and decent Jenkins an opportunity for reflection: a concert, a dinner, a writers’ conference, an air raid, a pub/nightclub crawl, a weekend in a country house. Characters come and go and Jenkins always seems to be in the right place at the right time, the narrative relies heavily on coincidences that usually (not always) manage to feel real and not too stage-managed, building up to form a kind of satisfactory shifting pattern.

As the novels progress we realise that we are being shown the ineluctable effects of Time, the entangled nature of destinies and the emergence of a narrative that shapes our lives:

For reasons not always at the time explicable, there are specific occasions when events begin suddenly to take on a significance previously unsuspected; so that, before we really know where we are, life seems to have begun in earnest at last, and we, ourselves, scarcely aware that any change has taken place, are careering uncontrollably down the slippery avenues of eternity.

Despite these novels being peopled by over 300 characters somehow we don’t lose the thread of who’s who as Powell reminds us of their connections and backstory. Even small parts deserve telling little pen portraits. (Colonel Budd, a very minor character, has ‘an air of total informality, as if prepared for any eventuality from assassination to imperfect acoustics’ – you can just imagine him.)

Aside from the core group of characters who define the structure and who shape and report on events, we meet pacifists; retired generals; publishers; hacks; subalterns; society hostesses; artists; dancers; actors; aristocrats; fortune tellers; sages; cads; academics; musicians; butlers; racing drivers; politicians; bankers; industrialists; film directors; students and playboys. In fact, far from being a one-track portrayal of upper class toffs, some of Powell’s best characters are from the demi-monde: the alcoholic novelist X Trapnel, the communist campaigner Gypsy Jones, the womaniser Dicky Umfraville.

It’s hard to think of a similar writer, but Powell has been likened to Proust, Henry Green, Evelyn Waugh and PG Wodehouse. It is true that his sentences can go on for ever, with sub-clause piling up on sub-clause, but Jenkins is nowhere near as self-obsessed as the narrator in A La Recherche; Powell’s tone is more hopeful than Green’s, less arch than Waugh’s and although social comedy is certainly there, he’s nowhere near as funny as Wodehouse. Taken as a whole, the sequence is a brilliant achievement – but the books don’t work individually and you can’t read them in the wrong order. If you start you will just have to continue so it’s quite a commitment, and you need to keep your wits about you. As X Trapnel comments, ‘Reading novels requires almost as much talent as writing them.’

Anthony Powell’s style is literary, measured, perhaps a little old-fashioned for modern tastes, and very English. He peppers his books with classical and artistic allusions which he expects his readers to be familiar with, and includes a few passages in French. Jean is described as having qualities ‘such as might be found in an Old Master drawing, Flemish or German perhaps’; Stringham’s taut features are likened to ‘Elizabethan miniatures: lively, obstinate, generous, not very happy, and quite relentless.’ Mrs Erdleigh, in a characteristically lengthy description, is:

‘Lighter than air, disembodied from a material world, the swirl of capes, hoods, stoles, scarves, veils as usual encompassed her from head to foot, all seeming of so light a texture that, far from bringing an impression of accretion, their blurring of hard outlines produced a positively spectral effect, a Whistlerian nocturne in portraiture, sage greens, sombre blues, almost frivolous greys, sprinkled with gold.’

The title of the whole sequence comes from Poussin’s famous painting which shows three young women dancing in a circle accompanied by Father Time plucking the lyre. The painting – which hangs today in the Wallace Collection – seems to suggest continual movement and yet a simultaneous sense of order and rhythm. Exactly like the books. These novels remind me a bit of a long running soap opera, or something more nuanced like The Sopranos, using the boxset techniques of jumps of time, where new seasons/novels show characters taking up ‘new positions in the dance’.

I first read A Dance to the Music of Time in my 20s, and coming back to them many years later has been an unsettling experience, like returning home after living abroad and finding everyone has changed. This time I am more interested in the middle novels and the older characters, and have noticed more in the books than I did before – the striving for creativity, the sadness, the themes of alcoholism and depression, the isolation of many of the female characters. It’s not perfect: some passages and episodes drag and the final novel for me doesn’t quite work – the characters are not as fully developed and the occult themes slightly heavy handed. Some of the outdated social attitudes and expressions will grate with today’s readers, even though they reflect worse on the speaker than the novelist (‘Every man should have 3 wives’… ‘She’s a nice little piece.’)

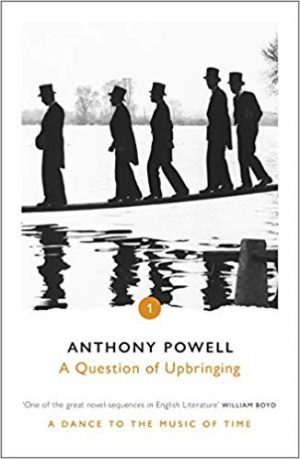

Arrow are re-issuing the books with new jackets – the final 6 out this December just in time for Christmas – which shows that they at least feel there is a new market to be tapped, although I’m sad they are dropping the wonderful Mark Boxer cartoons which adorn the covers of my volumes.

A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell is very much worth discovering if you haven’t yet taken the plunge: his is a vanished world and the books a remarkable chronicle of upper middle class English society over a period that saw huge changes. His characters may be of their time but you will recognise in it people you know, and you’ll come to appreciate, with Nick Jenkins, that ‘Nothing is more surprising than man’s capacity for survival.’

A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell is published by Arrow, 3200 pages!