A gripping, encompassing, little known play ‘about Africa’. Set amongst a violent uprising and liberation of Africans (in fictional Zatembe), still in the throes of casting off the shackles of white rule, Hansberry’s drama wields a extensive cast of characters from each sphere of the debate, confronting self awareness (or indeed lack thereof), culpability, guilt, anger, retribution and the cost of real freedom. Tightly written and constructed, it examines the meaning of sacrifice, guilt, justification and retribution; definitions of race and racism, of well-intentioned but romanticised notions of empowerment and freedom; and the inevitability and immutability of revolt. All of which she manages to weave with consummate skill into a clattering finale – a phenomenal voice that should be heard more often, even today.

The first preview of Les Blancs at National Theatre in London had the entire audience spellbound. It was consequently a rude awakening half way through when we were told that, due to technical difficulties, the play could not continue. With an addict’s urgency, I rushed home to read the rest of this monumental and significant piece of work.

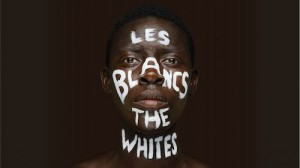

Set in the fictional African country of Zatembe during a time of post colonial uprising, the play Les Blancs is a multi-angled debate about Africa, about racism, the oppression of white rule and the struggle for independence that, uniquely, included an African voice.

The central character, Tshembe is the son of a tribe elder. He is an intellectual, what the tribe perhaps sees as a sort of lapsed Prince Hal, who has left the fold and travelled the world. On returning to Zatembe for his father’s funeral, he finds himself confronted on all sides for a call to action amidst a bloody revolution. His determination for inactivity – ‘It is not my affair anymore!’ -however seems to border on an inability to choose sides, an indecision resulting from his capacity to argue on both sides. References to Shakespeare are there: Hansberry even refers to Hamlet for his indecision (‘the Europeans have a similar tale which concerns a prince…’), although I think the compelling need for Tshembe to ‘lead his people’ to war is more reminiscent of Hal, shaking off a dissolute (in this case ‘white’) youth to take his rightful place as Henry V (to lead the tribe in the uprising against whites).

Nevertheless, though decidedly Shakespearean in it’s emotional complexity and tragedy, Hansberry consciously (almost self-consciously) roots the hero to an African narrative, focusing instead an old African story: the wise hyena Modingo (‘One who thinks carefully before he acts’) who ultimately loses the hyenas’ territory to the elephants by deliberating too long, incapacitated by indecision. Later, his brother Abioseh, the priest, also accuses Tshembe of inactivity and lacking faith even to himself:

Yes, Tshembe – but it is not I who am Judas! It is you who have sold yourself to Europe! It is I who chose Africa! Tshembe… I have watched you and listened to you and desperately wished that you would share my goals for our people. I have waited and prayed. But you believe in nothing! You act on nothing! You have put man on God’s throne — but you serve neither God nor man!

The play never seeks to over-simplify the issues at hand and, other than that there is clearly a need for action, there is no easy answer. Hansberry uses a fully varied and credible cast of characters, each vociferous but flawed, to provide the conflicting voices. The characters range from the ageing missionary who is perceived as a saint and father figure and yet he is only benevolent as long as the ‘natives’ behave as his ‘children’ and not speak to him of independence; an idealistic and naive American journalist, full of good intentions and romantic preconceptions of freedom, irritates Tshembe into responding: ‘I said racism is a device that, of itself, explains nothing. It is simply a means. An invention to justify the rule of some men over others.’

Other characters include Tshembe’s damaged younger half brother, Eric, and his fervently pious brother Abioseh, about to take his vows into the Catholic church; and a Major Rice, passionate about his right to protect the white settlers and full of solipsistic imperialism; the sympathetic Doctor DeKoven who nevertheless takes advantage of the vulnerability of Eric… and so on. Amidst all of them is Tshembe, harassed for his immobility by all the characters:

A man of your background could make a difference to your people…why don’t you speak out?… you must use the spear… your people need you… Our country needs warriors, Tshembe Matoseh. Africa needs warriors.

Despite his portrayal as a modern man, and a man of sound reasoning, it is Tshembe’s self-imposed isolation, both geographically and psychologically, and the consequent lack of taking a vital part in the movement that Hansberry condemns. In a speech before the play was even written she claimed: ‘The foremost enemy of the Negro intelligentsia of the past has been and in a large sense remains – isolation.’

Tshembe removes himself intellectually from all sides, all parties, and is constantly confronted by action from everyone around him. There may not be a ready answer to the questions poised by the play, but yet the message for action is clear. The ‘woman’ who repeatedly appears at moments of significance acts as a sort of spirit maiden, a mute warrior ‘angel’, that calls Tshembe to take up the spear (‘I have renounced all spears!’) and – to (mis)quote that other prince plagued with indecision – ‘to take up arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing them end them.’

I urge anyone in London to go see the electrifying Danny Sapani as Tshembe in Yael Farber’s haunting direction of Les Blancs at the National Theatre. [Click here: National Theatre – Les Blancs].

Les Blanc by Lorraine Hansberry is published by Vintage, 216 pages.