Bart van Es grew up with the knowledge that his grandparents had sheltered a young Jewish girl in the Netherlands during the war. As a middle-aged Oxford don he decides the time has come to find out more. This Costa Book of the Year winning book is the result: a remarkable blend of family history, wartime record and investigative journalism, where the secrets and lies of a family and a country are unearthed. The Cut Out Girl by Bart van Es is an astonishing piece of multi-layered historical writing in which we make the author’s discoveries alongside him, where artefacts and public records are examined alongside an old lady’s memories, and in which we learn anew about both the horrors and the sacrifices that humans are capable of.

In 1930s The Hague there is a build-up of racial hatred against Jewish families. Lien’s parents arrange via the Resistance for her to be taken in by a large Dutch family in the village of Dortrecht where she thinks she will be for a few months. She is 8 years old, and she will never see her mother and father again.

The van Es family is welcoming, practical and boisterous, and Lien gradually forgets her sadness and becomes swept up in her new life, until one day she confesses to a school friend that she is a Jewish girl in hiding. The police arrive and she runs, spending the next years in various other foster homes – some for a few days; others for months. Not all are kind – abuse and servitude live cheek by jowl with generosity of spirit – and Lien in the manner of displaced and unloved children everywhere gradually withdraws into a world of her own.

I think my main feeling was of having lost anything to hold on to. I was free-falling and . . . nobody could hold me.

Towards the end of the war she is able to return to the original family, and unlike Anne Frank – with whose story obvious comparisons will be made – she survives. The mystery of a later rift between Lien and her foster mother is one of the reasons the author has embarked upon his journey of discovery.

Lien’s wartime experiences are punctuated with Bart’s own process of investigating her story. He visits local museums and archives, the houses where Lien lived, talks to neighbours, relates other stories of Holocaust victims, even discusses the Dutch invasion of Java, Brexit, and current conspiracy theories. At times this feels a little patched together, even padded out, but the book’s architecture offers an insightful and compelling picture of a certain time in European history for which there seems to be an unending interest.

In 1940, when Germany invaded Holland, there were 140,000 Jews living in the country. 104,000 of these met their deaths in Auschwitz or Sobibor, the Nazis often aided by the willing collaboration of the organised and efficient Dutch. These horrors and Lien’s sad story are described in a starkly unsentimental prose.

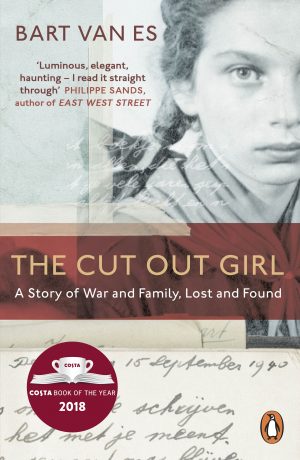

When the two of them first meet, Lien is in her 80s. She slowly gathers her wartime keepsakes for him: an autograph book, photo albums, documents. In one image her photograph is cut out and stuck onto another one. This is more than a metaphor for someone ripped from her home and displaced, it says something about her sense of not belonging, of survivor’s guilt, of a deep trauma that is still with her even now, and in part explains the family rift.

Bart van Es admits that writing the story has changed him. It will also change anyone who reads it.

The Cut Out Girl by Bart van Es is published by Penguin, 288 pages.