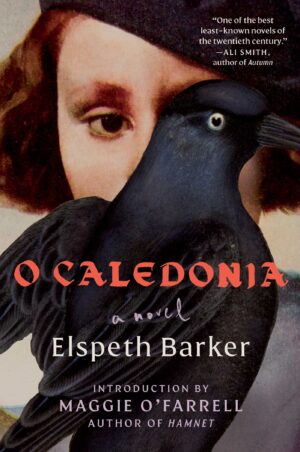

In surely one of the most captivating opening scenes in British literature, O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker, takes us to the vaulted hall of a remote Scottish castle. Here, in a crumpled heap on the flagstones, beneath a tall stained-glass window, lies sixteen-year-old Janet, dressed in her mother’s black lace evening dress, and covered in blood. Unloved and misunderstood in life, she has met a ‘murderous death.’ Moonlight filtering through the stained-glass picks out the legend Moriens sed Invictus; dying but unconquered. In Barker’s glorious and darkly funny portrayal of an outsider heroine’s short and intense life, the truth of this proves undeniable.

Janet’s parents, Hector and Vera, are not keen on having her interred in the family burial plot. She’d caused them enough trouble in life, they don’t want her blighting their eternal rest. After her murderer is dispatched to prison, they decide it’s best to forget their daughter and move on. Janet’s beloved pet jackdaw is the only living soul to miss her, searching for her ceaselessly, and finally ‘in desolation, like a tiny kamikaze pilot,’ flying on a death mission into the castle walls.

The story of how and why Janet’s life took such a peculiar turn, unfurls within the deliciously gothic walls of the family castle, Auchnasaugh. Having moved there as a young child at the close of World War II, it proves to be ‘all her soul ever yearned for,’ windswept, remote, and for this bookish girl, clearly the setting for Macbeth.

It already contains an inhabitant, Hector’s cousin Lila, a boozy, candle-burning bohemian, who spends her days reading, drawing and staring into space. Local gossip has it that she fatally poisoned her husband but Lila says he choked to death on a Fox’s Glacier Mint. Vera loathes her but Janet is prophetically drawn to this isolated eccentric, and divides her time between Lila’s room, voracious reading, and the beautiful Scottish landscape with its abundant flora and fauna. These meditative days come to a painful end when Janet’s parents pack her off to boarding school, with the aim of transforming her into a genteel young lady, just ripe for tweed suits and entry to society.

Despite the knowledge of Janet’s demise, it’s impossible not to root for her until the bitter end. She is trapped in what Proust has shown her is ‘l’etouffoir familial,’ the family suffocation chamber. Hector believes that girls are just an inferior form of boy and Vera finds the ‘unsocial nature’ of her daughter’s reading utterly depressing. They both actively dismiss Janet’s sparky intellect as boring ‘blethering.’ School is, of course, an utter horror.

Thankfully, the natural world surrounding Auchnasaugh provides sustenance for Janet’s soul. The humblest organism piques curiosity, the thrill of discovering an avenue of decidedly phallic mushrooms, ‘gleaming white and joyous in the fresh grass, an elfin priapic festival or a tribute to a fairy queen.’ Barker’s descriptive writing is sublime.

Only here in the far north does Janet feel alive again. She will not conform, and the story of her struggle and demise is perfectly cited in Maggie O’Farrell’s excellent introduction, as a ‘dark and glittering glory.’

O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker is published by W&N, 224 pages.